Practice makes perfect: glass artist Wayne Cain

Renowned glass artist Wayne Cain explains how his father influenced his own resourcefulness in learning and mastering a variety of skills, including stained glass, flameworking and bevelling – skills which have kept him at the top of the creative glass world for decades.

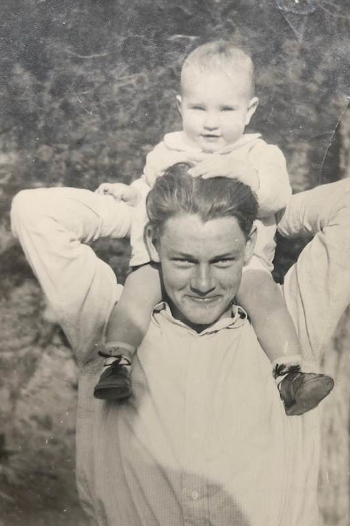

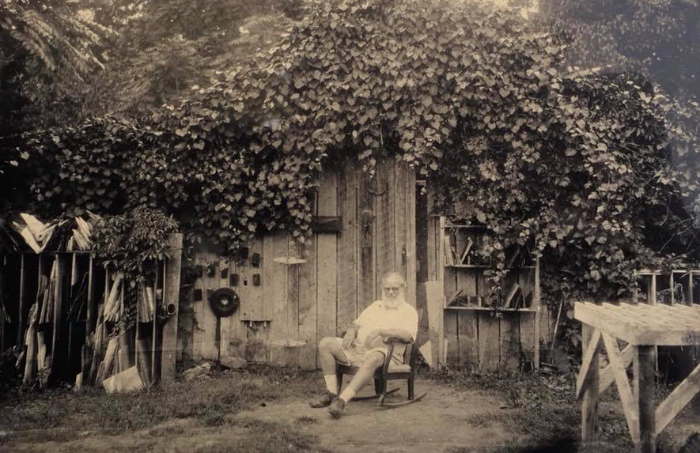

My father was known as a man who could do almost anything. He was a sheet metal mechanic by trade and would often take me with him when he worked on Saturdays, giving me tasks appropriate to my age and paying me 50 cents an hour out of his own pocket.

Soon after moving into our new home, which had just stud walls and insulation upstairs, my father informed my brother and me, aged about 11, that, if we wanted finished bedrooms, we would have to complete them ourselves: “I’ll show you the first step; you have to do the rest.”

Sure enough, he showed us how to hang one sheet of Sheetrock, how to tape one joint, trowel over it with joint compound, and cut and nail one piece of moulding.

I remember so well the emotional impact this had on me. I was quite upset that my father would not help beyond his initial instructions. Until this time, I’d had the impression that everyone worked together to achieve our goals. All of a sudden, I was faced with stud walls, some unfamiliar materials, and a few simple tools.

Another part of me saw the potential in my current situation. I was beginning to envision myself as an adult, someone who, in a few years, would be independent. I sensed that I was beginning to build a human being – myself – and that I could become the person I wanted to be.

The trial-and-error process came quickly and naturally to me: learning to drive a Sheetrock nail so it settled just below the surface without tearing the paper; applying just enough joint compound so the tape joint would end up flush with the finish surface; cutting the correct angle on moulding and sinking a finishing nail just below the surface.

The years I spent finishing off my bedroom stand out to me because I was on my own, doing and thinking. It developed in me a deep sense of self-confidence, knowing that I was developing processes that would help me when faced with the unknown later in life.

My father died of a heart attack when he was 43. I was 17. This devastating and final chapter in our relationship signalled to me that I was truly on my own and that I was responsible for my life.

The following year I was accepted into college. My family did not have money for such excesses, so I took our ladders and a couple of paintbrushes and painted neighbourhood houses, making enough money each summer to pay my way through. This was, in large part, a tribute to my parents for the self-sufficiency they instilled in me.

I thought a lot about how I wanted to live my life. I knew that I would not fit into the corporate world. I knew that I wanted to be compensated for the value of my development and not give it away to someone else. I also thought that one should work, make the money needed, and spend the remainder of their time enjoying the other things life has to offer.

Most importantly, I wanted to self-actualize. I wanted to apply my problem-solving skills to the real world.

Out of college, I thought about becoming a blacksmith, perhaps a copper smith. I was also fascinated by light filtering through treetops, the translucency of nature.

This love of light helped me decide, in June 1972, to climb into my 1964 VW bus and drive from Richmond, Virginia, to Rockland, Massachusetts, to the Whittemore-Durgin Glass Company. I remember sleeping in my bus to save every cent I could to buy the basic tools and materials I needed to begin my chosen journey of working with glass.

Starting on the kitchen table, I made stained glass apples, pears, cherries and chickens that stood on one leg, selling them at craft fairs and gift shops. From there, it was ‘Tiffany’ type lampshades, windows – including learning how to repair both – as well as curved shades.

A local plate glass company offered to sell me their 1915 Henry Lang bevelling machines. At the time, I couldn’t find any literature on how to bevel so, once again, I relied on the trial-and-error process.

Holding a piece of glass over rotating iron, stone, cork and felt was not the most exciting pastime. In order to hold my interest, I began grinding and polishing different thicknesses of glass with different angles. I bevelled flash glass, coloured glass, and textured glass and made a display case to carry around. This was in the days before the Internet, when artists walked around with large portfolios. I loved opening it up to clients, who instantly realised that I had something special to offer them.

A wonderful thing about being self-taught is that one doesn’t know when to stop. I also developed bevelled glass windows with thicker glass so my windows would ‘hold their own’ when surrounded with oversized wood mouldings. Then it was on to UV-gluing beautiful, deep, rich colours of antique glass behind my bevels, giving them a jewel-like quality. This led to my contemporary bevelling style.

Carving, painting, and fusing soon followed. I loved the experimentation, being able to quickly test an idea by trial and error. When I look over my life’s work, the one thing that really stands out to me is the diversity of styles and techniques. I attribute this, in part, to how comfortable I am with dealing with the unknown and working with a variety of clients who have led me in different directions.

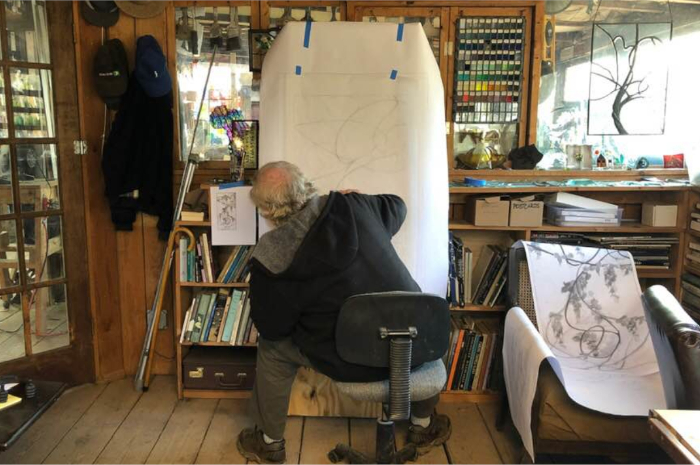

Around 10 years ago, I began to renew my interest in the translucency of nature. I was also tired of wrapping each piece of glass in lead and foil, further restricting the light. I started introducing flame-working into my windows. I wanted to work in a painterly way, placing the flame-worked pieces onto the background glass and seeing how each piece of glass looked before permanently attaching the leaves and petals.

Flameworking was a slow, painful process to learn. If you count the time invested working over a flame, squeezing, mashing, and pulling a melting strip of glass, it was also a very expensive process. I know it took years of working in my spare time before I had the various shapes and colours, and a reasonable production time, to begin seeking commissions.

I remember showing a tour of 12-year-old students baskets of my flame-working rejects during a demonstration in my studio. For a second, I thought their eyeballs were going to fall into my collection.

With the ability to form delicate shapes and colours and to work in three dimensions, I was finally able to work in a way that I had envisioned 47 years before.

Our latest innovation is creating branches with wire and solder and attaching them to the branches in our window design, adding even more depth to our windows. Suspending leaves and petals out on the ‘branches’ gives a realism that has exceeded all our expectations.

It is very difficult making a living as an independent artist/craftsperson. Some days, I feel like a corporation reduced down to one individual. It’s not only the expertise that must be constantly developed, but also the peripheral skills, like marketing, selling, website development, purchasing materials, making presentations, taxes, insurance, social media, communication, organisational skills, and working with the people who help us produce our art.

In the early days, people were very secretive about their work: “Don’t take photographs of my work”; “You stole that idea from me”. Now, for the most part, we live in a world where people freely share their ideas. Maybe not their closest secrets, or their client list, but there is an enormous amount of material available to everyone. I am especially fond of YouTube and specialist social media groups where one can share an experience and people from all over the world respond.

The Internet has made it possible for people to commission us from all over America. Working with photographs, email, postal service, and freight companies, we rarely have to leave our studio. This is a far cry from the days when we lugged around large portfolios and glass samples to meet with people who didn’t understand why a commission window cost more than $49.00.

In my shop, everyone has the power of influence. If someone has an idea, a quick study is made, and we all share our thoughts. It is the same process I learned when finishing my bedroom. Thinking and doing, trial and error. Every line, every colour is carefully considered. We take risks – a lot of them – always hoping to discover something new.

We never use the word ‘mistake’. Our brains move so rapidly: we just know if something is not right. We work intuitively. There are billions of neurons in this three-pound organ between our ears, processing information in milliseconds. It is the “control tower” of our being, providing split-second insight that we often call creativity.

In my studio, we harness this gift by giving it the time and space needed to function with the least amount of interference. Insights that take flight into the conscious are quickly written down and later transferred to a large sheet of pattern paper. From there, they find their place in the many categories and flowcharts we use to organise our work.

All of us in the studio work the same way. I may be the only one taking notes, but I am constantly listening and encouraging the free flow of ideas that provide the basis of our creativity. It is also the reason why everyone here deserves the right to sign each of our creations.

Our working relationship has also given us a new language, one that is often unspoken, where thoughts are quickly communicated in many different ways. I often think of it as communicating in a negative space, like the negative space in a work of art: powerful once discovered.

I believe that working in this way is very human. This is the way we have evolved over thousands of years to manage a complicated, ever-changing world. It also accounts for our needs for diversity, community, and good communication skills.

The other trait I believe necessary to succeed as an artist/craftsperson is perseverance. There are certainly less difficult ways to make a living, and we are all too often seduced by easier jobs, higher pay, and benefits. But there is nothing as fulfilling as assuming responsibility for your own development, then making a living based on what makes you unique.

Written by Wayne Cain

Main feature photo: Wayne Cain applying flame worked flowers and leaves to a design.

All photos supplied by Wayne Cain.

Read more about Wayne Cain on his website: https://www.waynecain.com