Judith Schaechter – stained glass innovator

The renowned US glass artist speaks to Glass Network digital editor, Linda Banks, about her career, techniques and inspiration.

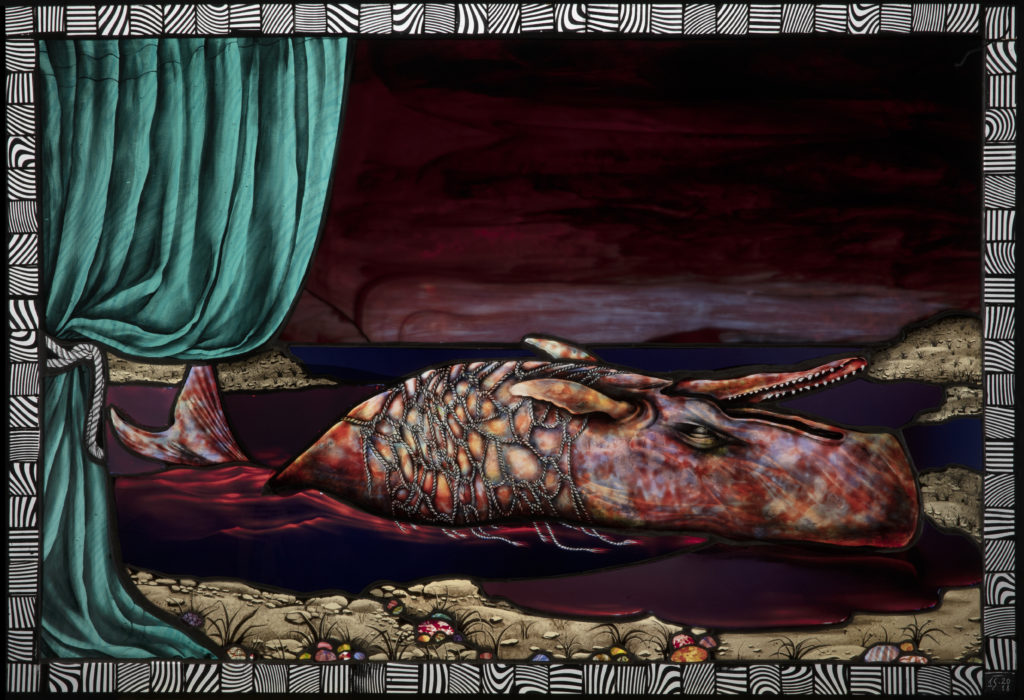

Stained glass has been with us for centuries and, over that time, the methods of construction have changed little. Americans Louis Comfort Tiffany and John La Farge introduced the use of opalescent glass and layering for windows towards the end of the 19th century, but Judith Schaechter has pushed the boundaries further. Her stained glass practice has evolved to include a meticulous engraving process and layering of up to five pieces to achieve the great richness of tone and colour seen in her arresting work.

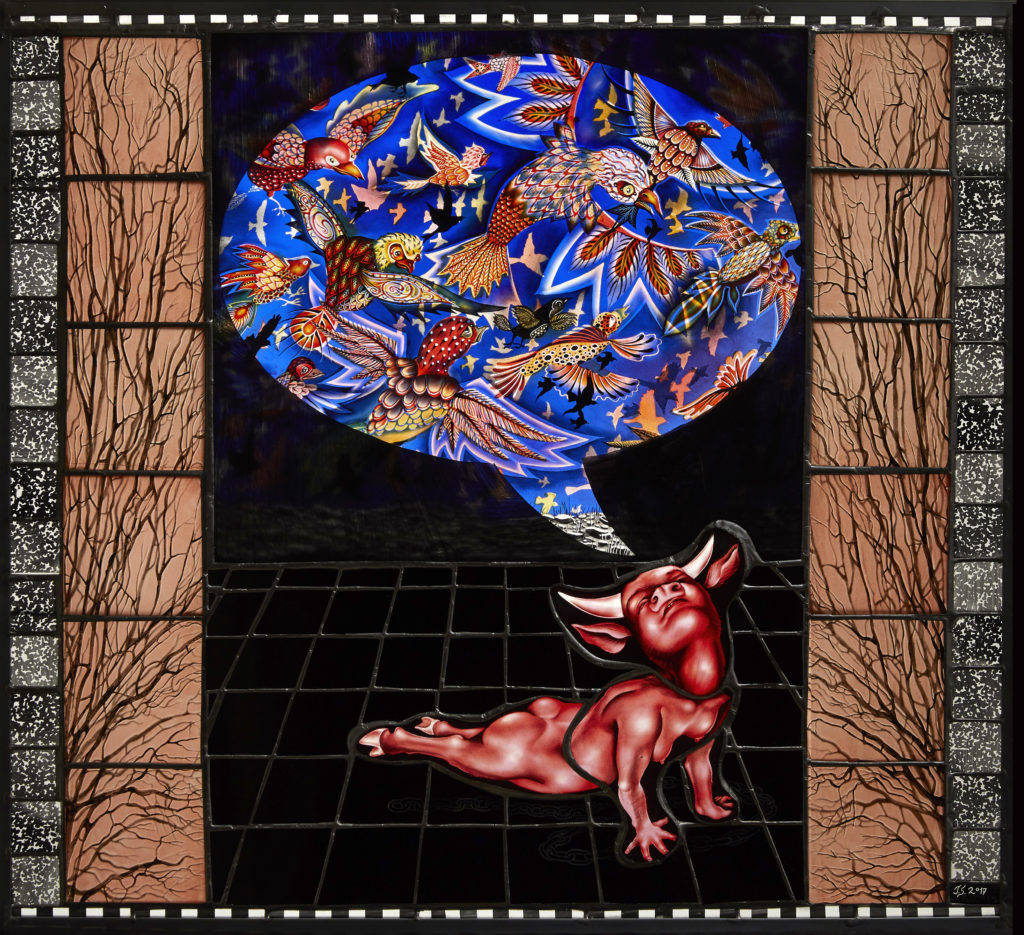

Judith says people often comment on her subject matter as being ‘negative’ or ‘difficult’, but she doesn’t find her work negative or difficult at all. She quotes from an essay called ‘The Art of Unhappiness’ by James Poniewozik (in the January 17, 2005, “Happiness” issue of Time Magazine): “What we forget … is that happiness is more than pleasure sans pain. The things that bring us the greatest joy carry the greatest potential for disappointment. Today, surrounded by promises of easy happiness, we need someone to tell us that it is OK not to be happy, that sadness makes happiness deeper.” She wants to be that someone!

You have worked with glass for 37 years. Has your outlook changed over that time? What motivates you?

When I first encountered glass, and for several years thereafter, I thought I had finally found the thing in this world that would never bore me. I didn’t know it then, but I have attention deficit issues. I had worked in oil paint, sculpture, sewing, guitar playing, but I just couldn’t attach emotionally long enough to learn much in those other areas. I was always bouncing around. And when I hit a wall with something, I just moved on instead of working through it.

Stained glass began as the most enthralling version of being in sync I could imagine. That has faded over the years, but I was able to get to a point of fluency with the material to the point where it didn’t matter if I was glitteringly inspired or not. I could still find a way into emotional attachment and productive exploration. And yes, I still love it!

You use several different techniques to create your designs. How did these evolve from the traditional methods you were taught?

I was taught by Ursula Huth, who was a student of Hans Gottfried von Stockhausen, a professor at the Stuttgart Academy. Her method was traditional in some ways but focused on making ‘autonomous panels’. She was very strict, and I learned mostly traditional methods of cutting and assembling with lead cames. Everything else was pretty cutting edge. I learned about sandblasting flash glass from the outset.

I have always been focused on what is called ‘narrative’ image making (I put that in quotes because narrative implies a story tome and I usually don’t have a story attached to my pictures).

When I began, I relied mainly on sandblasting using hand-cut stencils. I gradually introduced glass paint, but with little or no instruction that I recall. I was putting down a wash of black and scratching into the glass with craft knives exclusively, having never learned about matting and tracing.

One day I accidentally sandblasted a surface intended for painting and that was when I began using the rough, sandblasted surface to create graded paint tones. The idea of layering the flash glass evolved pretty slowly over the years and was partly inspired by seeing pieces of glass piled up in the corners of my light table.

The idea of using diamond files to create the smooth gradated tones which, I think, are a hallmark of my work, came from recognising that the diamond burrs I was using in the flexible shaft engraving tool did not need electric power to mark the glass. I discovered the files (originally for bead makers) at a stained glass conference. They give you a lot of control and I really enjoy the technique, but it is extremely slow!

Can you describe your making process?

I use flash glass, which is a glass with a paper-thin veneer of intense colour on a base layer of lighter colour.

First, I cut the glass using a steel wheel cutter and grozing or running pliers. The next step is sandblasting. This process removes the coloured layer, sometimes in stages, to get patterns and tones. After sandblasting, I engrave smaller details using a flexible shaft engraver. I use diamond files to make smooth variations in the colour.

The only paints I use are tracing or stencil black and silver stain. I usually do 2-5 firings, as that is the best way to get rich blacks and greys. After the firings are all done, I sometimes get a little additional colour with thin washes of transparent oil paint. This is all the paint I use and all the other colour is the flash glass. Once the paint is fired on, I sometimes engrave or file it as well.

One reason there is a lot of colour in each section of my pictures is that the flash glass is layered, sometimes up to five pieces deep.

Flash glass and the diamond file are my favourite tools and materials because they liberate my soul into the cosmos!

Where do you get inspiration for your designs? How do they start?

Inspiration is a word that we only think we understand. For me, it is never step 1. Inspiration is an emotional state that can happen at any point in the process and probably later is better. If I am inspired at first, I will surely not be later!

My pieces start almost always as doodles. I mean, once upon a time, I used to have what someone might call an ‘idea’. I would think, “I should do a piece about such and such a topic” and I would record that thought, in words, in a list in my sketchbook. But that hasn’t happened in decades!

Now, I find a drawing that interests me, and I make it in glass. I put it in a storage bin and wait for a resolution to arise organically. I do not want to force them. Sometimes the glass parts cross-pollinate with each other and resolutions crop up that way.

I also work with images in Photoshop to generate many possibilities, which is a drawing/collage process, but can be translated into glass if anything interesting arises. As I get older and more experienced, I find it is much more important to create opportunities for being spontaneous with the glass. I want to improvise directly with the material and let that dictate the results, not interpret a drawing.

The images I draw come to me automatically. Now I will say, I feed my imagination an extremely rich diet of cultural artefacts, including art, but stuff I encounter on the internet, maybe a smattering of the natural world etc. This brews and steeps until stuff comes out in the form of drawing. Automatic drawing is a process that the Surrealists used to introduce chance and improvisation into their work.

As I said, I try very hard not to start with an idea and I try to keep my work free from any preconceptions. Basically, in a nutshell, I have no idea what I am doing, no idea what I am going to do next, or where the piece is going, until it’s done! Then, with hindsight, I can trace the work from its genesis to its completion.

What response do you want to evoke from the people who view your work?

Well, I suppose Stendhal Syndrome would be ideal if I get to choose! [Stendhal Syndrome is a psychosomatic condition involving rapid heartbeat, fainting, confusion and even hallucinations, allegedly occurring when individuals become exposed to objects or phenomena of great beauty.]

Most of the time an artist does not get to be present when the artwork is being looked at. And only extremely rarely will anyone say anything negative to one’s face. Of course, I like hearing people say they like my work! But I have accidentally overheard some nasty stuff and I have to say, it was pretty funny for the most part.

Speaking generally, I hope that my work is a comforting and even healing experience for those who can relate to it.

Can you choose a piece that has given you particular satisfaction? Why?

I usually like the current work best as the older work starts to feel like some other person made it. A recent piece I am particularly pleased with is ‘The Life Ecstatic’. I think it works on many levels, including emotional and technical.

How did you establish your glass studio?

I wasn’t going to at first as it seemed too daunting, especially given my utter reliance on sandblasting. But I missed it too much, so I plodded forward small steps at a time. Stained glass is actually a really easy DIY home set up if you want it to be. But the sandblaster! That required homeownership to accomplish! Then I had to find someone who could actually set the darned thing up for me.

What was your first big break in your career in glass? (no pun intended)

Hahaha!! In 1989, I broke a piece right after soldering it because I leaned it up in a window and it fell. I had to remake the entire upper portion and it took over a month!

But actually: I came to Philadelphia, joined a co-operative gallery and exhibited there for 10 years. During that time, I tried to get a New York gallery to represent me with no luck. But I did apply to the Corning Museum of Glass’ New Glass Review and that got my work seen by important curators, such as Susanne Frantz and Michael Monroe. They included me in some exhibitions, including one at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian.

How do you promote and sell your work?

I work with Claire Oliver Gallery in New York City. This fine art gallery represents several artists by giving them exhibitions and showing their work to potential collectors, as well as promoting the work to curators and showing it at art fairs.

What advice do you have for contemporary glass artists starting out today?

My advice would be to always do what you love. That way, if the whole enterprise goes south, at least you enjoyed yourself a wee bit.

What standing does contemporary glass – and stained glass in particular – have today, compared to other creative disciplines?

I think, right at this moment, this is a very hard question to answer. I have said previously that the medium suffers from art vs craft issues and that most stained glass doesn’t try very hard to be art anyway. That’s still true, but now I think the art world is in a much bigger state of crisis and uncertainty that ever before. Who knows what stained glass will be when art disappears! Hang in there, stained glass, this could be your moment to pounce and fill the spiritual craving gap caused by art’s gradual abdication from existing (maybe more in the USA).

Who do you see as pushing the boundaries with stained glass today, apart from you?

Masakubi Nakamura, Sasha Zhitneva, Angela Steel (Scotland), Karisa Gregorio. I really love Tom Denny.

But beyond pushing boundaries, why not strengthen the centre? Here you might find artists such as Richard Prigg and Glenn Carter.

Who are your heroes?

The closest person I have to a hero would be punk rock artist Patti Smith because she was a brave female artist who was uncompromising and brilliant.

There are plenty of people I admire, my mother (who died in 1988) for one. I also feel intense gratitude towards my teacher Ursula, Richard Harned at Rhode Island School of Design, as well as the curators and galleries who have helped me to have a career.

Have COVID-19 and the rules on self-isolation impacted your working practice and creativity?

Yes indeed. Although I have worked for 35 years by myself and out of my home, and although my studio is well stocked and I adore solitude, these times are not as productive as I would have imagined, as I am pretty much constantly worried about whether or not society as we know it is going to collapse. Creativity is only enhanced in these times right now for those who are able to be in total denial. Everyone else is too concerned and baffled by an uncertain future!

Hear from Judith herself in this YouTube video by Floating Home Films.

Feature image: ‘Three Tiered Cosmos’.

About the artist

Judith Schaechter has lived and worked in Philadelphia since graduating in 1983 with a BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design Glass Program.

She has exhibited widely, including in New York, Los Angeles and Philadelphia, The Hague in the Netherlands and Vaxjo, Sweden.

She is the recipient of many grants, including the Guggenheim Fellowship, two National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships in Crafts, The Louis Comfort Tiffany Award, The Joan Mitchell Award, two Pennsylvania Council on the Arts awards, The Pew Fellowship in the Arts and a Leeway Foundation grant.

Her work is in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Hermitage in Russia, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Corning Museum of Glass, The Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution and numerous other public and private collections.

Judith has taught workshops at numerous venues, including the Pilchuck Glass School in Seattle, the Penland School of Crafts, Toyama Institute of Glass (Toyama, Japan), Australia National University in Canberra Australia.

She has taught courses at Rhode Island School of Design, the Pennsylvania Academy, the New York Academy of Art and at The University of the Arts, where she is ranked as an Adjunct Professor.

Judith’s work was included in the 2002 Whitney Biennial, a collateral exhibition of the Venice Biennale in 2012 and she is a 2008 USA Artists Rockefeller Fellow. In 2013 she was inducted to the American Craft Council College of Fellows.