Enhancing life with enamelling

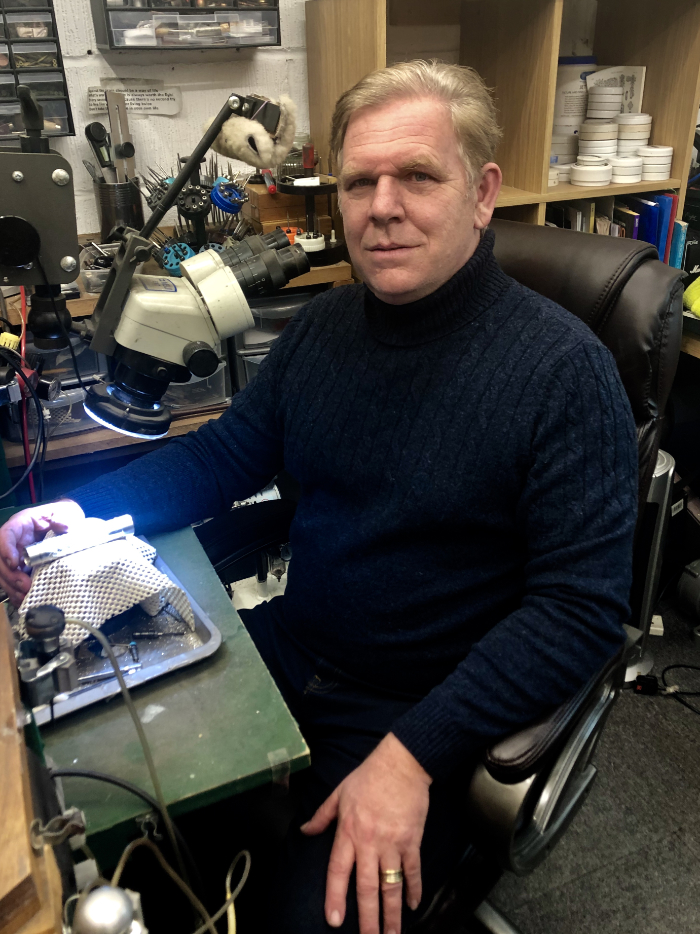

Harry Forster-Stringer transforms jewellery, functional forms and art objects with fused, powdered glass in a myriad of rich colours. Here he explains his journey into enamelling, and the inspiration behind his designs, to CGS Glass Network digital’s editor, Linda Banks.

You have been a jeweller for many years and use enamelling in some of your work. How did you first become interested in enamelling?

I learned a range of techniques during my jewellery apprenticeship. My interest in enamelling was rekindled when I was asked to give some summer classes at the Birmingham City School of Jewellery. One of my students was the enameller Rachel Gogerly, who was chairman of the Guild of Enamellers. Sadly, she is no longer with us, but she was a huge inspiration to me.

Rachel asked me if I would give a joint masterclass on engraving alongside the master enameller Phil Barnes. Seeing Phil and Rachel’s work ignited a fire in me and I just knew it was something I wanted to do.

There are various enamelling techniques. Please describe them and the different effects they achieve.

The main enamelling techniques used today include cloisonne, which uses thin wires of copper, silver or gold to create sections, plique a jour, which also uses metal wires to create individual cells, but has no backing so the light can shine through, and champleve.

The technique I use most is champleve. This involves carving the metal that will support the enamelling to the depth that I require, then cutting a pattern, which helps to reflect the light and allows movement within the work.

Through Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust (QEST) funding you were able to work closely with the late Phil Barnes, who was widely seen as the master of enamelling processes. What did you gain from this experience?

I was very lucky to gain a QEST scholarship in 2017. This enabled me to work under the instruction of the master, Phil Barnes. I feel so grateful that I had the opportunity.

Prior to this, I had been enamelling my jewellery and others’ work, but I wanted to know how to do this on a larger scale. This would enable me to start making work that was more artistic, rather than functional or for adornment.

After my first lesson, Phil called me and insisted that I stay at his home with him and his wife Linda. He wanted me to grow my knowledge all the time. Even near the end of his life he would call to give me advice about how to resolve specific problems. A very important lesson I learned from Phil was ‘fail to prepare, prepare to fail’. This tip is highly relevant to enamelling.

Towards the end of his life, Phil invited me and another enameller he knew to come over. He had divided his tools and enamels and wanted to give them to us. It was a very emotional moment, but, even now, when I’m having a bad day with my enamelling, I still take comfort from Phil, as he is in my head with all that advice. I will always be grateful to QEST and Phil Barnes.

What is your creative approach? Do you draw your ideas out or dive straight in with the materials?

The quick answer is that inspiration usually comes five minutes before I fall asleep. However, my creative process is probably founded on a more complex background of experience. I was born in East Ham at the start of the 1960s but, by the time I was five, I was living in Karachi, West Pakistan and, later, in Dacca in East Pakistan (now known as Bangladesh). We travelled all over India and Nepal, so at a young age I was immersed in culture, the sacred geometry, vibrant colours, and even the clarity of the water running down the rivers and streams of the Himalayan mountains. I was absorbing everything, and I think that’s why shapes are so important for me and are my starting place. Once I can see something in my head from all angles, I’m ready to start. I do a few rough drawings and then develop the idea from there.

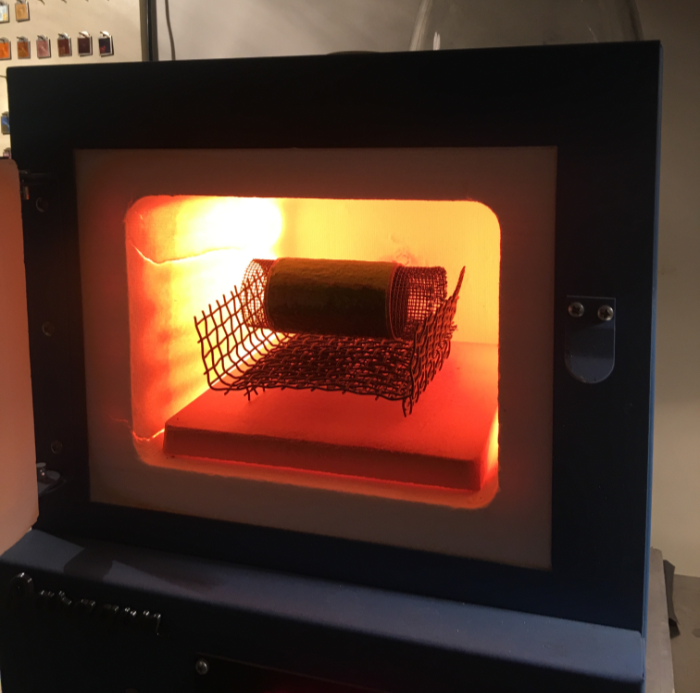

What is your favourite enamelling tool or piece of equipment and why?

I don’t really have a favourite tool for enamelling. They are all important, depending on what you are doing. However, I do love to watch the enamel cooling after firing and seeing the different colour changes until it settles to its final colour.

Do you have a favourite piece you have made? Why is it your favourite?

One of my favourite pieces is the Bendicks box, possibly as this is something Phil saw and praised. Bendicks have a royal warrant because the Queen is a fan of their mint chocolates, so I thought that this design needed to be regal.

I added a crown to the top and realised I had not made a tower with a crown, but rather a good old post box! Somebody else had beaten me to it!

Overall, I like each piece I have made until the next one comes along.

What advice would you give to someone wanting to start working with enamels?

Ideally you should find someone who knows what they are doing to give instruction. If you are going to teach yourself, you need a benchmark of what is good. The V&A Museum in London is a great starting point, as it has lots of great enamel, created using different techniques. However I recommend investing in a couple of lessons on how to prepare the enamel and lay it, as this will save a lot of time in the long run as you need a lot of patience and perseverance. Enamelling is not as easy as you might like to believe.

Do you have a career highlight?

My career highlight was meeting Rachel Gogerly and Phil Barnes. If I had not met them I would not have ignited the passion to get better at enamelling. In terms of enamelling, my highlight was achieving a QEST scholarship and then being able to work under Phil Barnes’ guidance. That experience saved me years of trial and error. A further pinnacle was meeting all the people at QEST, who have been, and continue to be, a massive support to me.

Where do you show and sell your work?

Most of my work is commissioned through word of mouth or referral from the jewellers and designers I work for. At the moment, I’m doing a lot of work for other manufacturers. Before the pandemic I was doing a lot of events organised by QEST, which worked well for me.

Who or what inspires you?

My biggest inspiration is Phil Barnes, who was a fantastic teacher and, more importantly, my friend. He was my ‘big brother from another mother’. Plus, I must not forget Rachel Gogerly, who was the key who opened the door to my passion for enamelling. They both have a special place in my heart.

Did the coronavirus impact your practice?

Yes, it had a massive impact on the jewellery business. Anyone who has ever tried to take pictures of enamelling will know how difficult it is, and it really must be seen in person to appreciate its real beauty. Everything just came to an abrupt halt.

The pandemic did affect my mental wellbeing initially. I lost my way a little, as it felt like a dark tunnel without end. However, when I thought of others who were in a much worse situation with their loved ones, it brought everything into perspective.

Thankfully life is getting back to normal slowly. However, people’s shopping habits have changed, so it may take a little while. The good thing that has come from it is that people are more involved with art and crafts again, and I have been doing a lot more teaching since the rules relaxed.

In conclusion

The passing on of knowledge is crucial in craft. Knowledge that has been given by a master can date back thousands of years and will go forward for thousands of years, as long as the chain is not broken. Through sharing skills, a little bit of you goes on forever.

Find out more about Harry Forster-Stringer and his work on his website: https://www.harryforsterstringer.com

Main feature image: A hand-carved paperweight featuring the theme of night and day, beginning and end.